I saw a Twitter post today that had been reTweeted more than 18,000 times and liked more than 17,000 times, with more than 400 comments. The post was about how King Leopold killed more Africans than Hitler killed Europeans – good point (we can quibble about specific numbers, but the point is valid and thought provoking). The second part demanded to know why were weren’t be taught about this is in schools and that’s when I felt defeated. With a simple retweet, thousands were immediately voicing disappointment, if not outrage, at educators across the country. I felt defeated because I go very much in depth on Leopold and the genocide in the Congo, and also the African Holocaust. The tweet may be an accurate criticism of a particular teacher, or maybe even school district, but I was also lumped into this grouping. I wonder if this person reached out to their school district or social studies teachers before reaching out to social media? I am not angry with the tweeter – I want to thank her for opening an important conversation, for knowing her history, for her courage in sharing, and for her passion. This gives me a chance to blog about the importance of bringing home and school together, and why social studies is complicated. I will share my lesson plan and resources on this immense tragedy at the end of this post.

When I signed up to take the social studies teacher exam as I began to plan for my career in education, I wondered how I could possible prepare for this all inclusive exam. I finally decided that there was no practical way to fully prepare as the exam could have questions from ANYTHING in history. Think about it. Any possible historical topic could be on the exam, from any point in time, and from any place on earth. Not only that, the exam would also have questions on economics, religion, culture, geography, psychology, pop culture, art, gender studies, astronomy, science, music, political structures, civics, etc. I can be asked to teach any social studies course, grades 7-12, and I have taught many. Don’t get me wrong – this is why I love being a social studies teacher as I can teach anything. I open up my class every year with a discussion on “what is social studies?” as I show students pictures on a PowerPoint and ask them to write down yes or no, then explain why. I show them a hip hop video, a movie trailer, pictures of comic books, drawings from major battles, maps, social media images, images of the universe, sports players, etc. I then ask them to discuss with their partners why they answered yes or no for each answer. I am always fascinated by their discussions and do not interfere with them and say that all answers are valid. When we come back to a full class discussion, I then tell them that the “right” answer for each is YES. Everything is social studies – be it from thousands of years ago or what happened moments ago. I hope you can now have a better idea as to the wonder and terror of teaching social studies, as my students often tell me that I blew their minds.

I am going to use the example of the previously mentioned to tweet to explain how we can tackle this issue and make it an amazing benefit for our students, our parents, our community, and for social studies teachers. We all have a textbook, a curriculum, and a course title to guide us throughout the year so that we don’t just immediately shut down when tasked to teach a course. This year, I teach Modern US and Modern World to high school students. As a past teacher of European History and World History, I thought Modern US would be so easy because the content was much more defined. However, my greatest strength, and weakness, is that I like to go down the rabbit hole of history – I like to explore and make connections. I think it is so important to not “just” teach about the Civil Rights Movement in terms of the 60s, but also to explore modern civil rights leaders – in LGTBQ+, mental/physical disability, Latino, Japanese-American concentration camp victims, etc – and also to those in the past who fought for gender equality, historical struggles of the impoverished, etc. When I teach about 9/11, I begin with the Crusades, focus on WWI and its impact, and end up with “terrorism” in the world today. Everything is connected and we need to understand the historical impacts on the world of today. Right now, you may be wondering why I didn’t mention _______________ in my listings above. This is the heart of the issue – the more I try to encompass everything, the more I feel I leave out. Allow me to get back to the tweet and my lesson about King Leopold.

When I begin teaching about the Jewish Holocaust, I ask my students to write down what they know about the events in general, and how many Jews were killed in particular. I am always impressed with their background knowledge and that many can tell me that about 6 million were killed. I then ask students how many were killed in the African Holocaust, Native American Genocide, and Holodomor. This is where the room gets quieter as the students are not sure of the answer when they discuss in small groups. Very few have ever heard of the word Holodomor (this word continues to not even show up in spell check) and they begin to ask questions. This also then leads us into a discussion on the terms genocide and holocaust and how they may be misunderstood or applied (as I did here). Some students even ask why they had never been taught these ideas before, and as part of the discussion, I bring up how some folks even believe that the Jewish Holocaust did not happen and that Jewish groups are just pushing their agenda, to you know, take over the world and stuff. I quickly point out that so many Jewish organizations are the ones leading the charge about genocide in general – not “just” about the history of Jews. I then made it my mission to teach about several genocides alongside the Jewish Holocaust and to make connections between all off them and the lessons we must understand. I thought I was doing my due diligence in expanding the knowledge base of my students and was proud of not just following the textbook. I was also determined to go in-depth on the genocide in the Congo with a multimedia presentation, primary sources, etc. Then, in one class, a quiet young woman spoke up, I had not heard much from her all year, and she asked – “what about the Armenian Holocaust? My Dad was angry that we weren’t learning about it.”

Immediately I saw the flaw in my thinking – by trying to widen my approach, I had opened minds, and now everything was on the table – and I mean this in the best possible way. To my credit, I acknowledged the “failure” in my approach and said that we would scrap my initial plans and brainstorm on how to approach this “complication.” WE decided to research a list of genocides in history, form groups, and teach each other about them. I would teach about the genocide in the Congo, other students would pitch me ideas and present on events where they felt connected. After all of my classes did the initial research, the list was shared between all four classes, and we came up with a game plan on how to research, what needed to be in the presentations, etc. WE then had it all formalized into an assignment sheet and it was sent home with a written explanation. WE asked parents to give input, to let us know of any other ideas that they might have about events in their own cultural backgrounds. So many students came into class excited to tell me that they had no idea that this had happened in so many other places in the world and that they couldn’t wait to do the research. I told them that I would present on the Congo Genocide and would do the research and work alongside them.

The presentations were amazing and I learned so much from my students. Most importantly, I learned that I didn’t have to shoulder the responsibility to know EVERYTHING in history -that I had classes full of motivated researchers in front of me every day. I will now leave this assignment open every year for topics and I have broadened this approach to everything I teach. I put this on my class syllabus that goes home and I say it to parents on back to school night – please let me know what you think we are missing. If you have a personal connection to history and want to share, let us know. If you think I missed something important, let me know. I will do my best to teach about a broad range of topics, but I can never cover everything and I cannot possibly know everything.

To bring this post full circle, I would encourage the author of this Tweet, and you, to reach out to your schools and teachers when you have similar thoughts and feelings. History is passionate and important to everyone – we need to build a community where we can learn from one another. If you don’t get a response, then take other actions. But please, I implore you, reach out to the teacher first. When we take to social media first, we confirm often wrong assumptions, something I try so hard to make sure my students never do. Just because you or your child didn’t learn about something in your class, doesn’t mean others aren’t doing a great job. Perhaps this teacher missed this point, but does amazing things on other topics. Just give them the chance to learn with you and your child. Education is a boat we are all surely in together and we all want what is best for our students. I never want a student, or parent, to feel that they are marginalized or ignored in my class. This is also why I allow my students to choose their own topics for the research paper, but this is a topic for another blog.

Below are some of my resources for teaching about Leopold. It is difficult to fully translate the full classroom experience and our discussions, but I tried to give some highlights of the lesson below. Much of my information comes from King Leopold’s Ghost by Adam Hochschild

Step 1 Do Now –

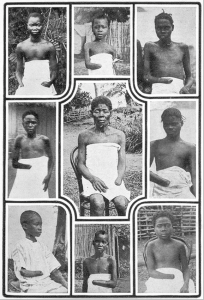

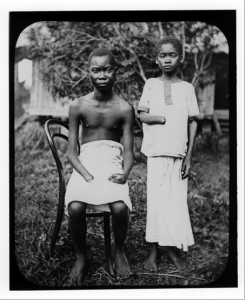

- Interpret the following poem – think – who was Leopold? Why would he be burning in Hell? How does the poem tie into the picture? What questions do you have/want to know more about?

“Listen to the yell of Leopold’s ghost

Burning in Hell for his hand-maimed host,

Hear how the demons chuckle and yell

Cutting his hands off, down in Hell.”

– Step 2 – set geographical context. How can such a small nation come to enslave a much larger nation?

– Step 2 – set geographical context. How can such a small nation come to enslave a much larger nation?

Step 3 – Why were the hands cut off? State officials would see to it that the victors severed the hands of dead warriors. During expeditions, Force Publique soldiers were instructed to bring back a hand or head for each bullet fired, to make sure that none had been wasted or hidden for use in rebellions. A soldier with the chilling title “keeper of hands” accompanied each expedition. Force Publique soldiers were slaves who had been press-ganged through hostage taking or stolen as children and brought up in child colonies founded by the king and the Catholic Church

Step 4 –  we now discuss what else we see in this photo. I have students create questions about it. I let them brainstorm and we discuss. One of the most important questions is often overlooked – who took the picture and why? When I put this question to the class, their conversation takes an entirely different course as we try to figure out the purpose of the picture. These photos were taken to counter King Leopold’s powerful propaganda machine and his being reinvented as a Christian philanthropist.

we now discuss what else we see in this photo. I have students create questions about it. I let them brainstorm and we discuss. One of the most important questions is often overlooked – who took the picture and why? When I put this question to the class, their conversation takes an entirely different course as we try to figure out the purpose of the picture. These photos were taken to counter King Leopold’s powerful propaganda machine and his being reinvented as a Christian philanthropist.

Step 5 – I then read some excerpts from Ishmael Beah’s A Long Way Gone to make a connection to more current events in the same area of the world. I then ask the students why – what did the Europeans want from these people then and today? I explain that Leopold wanted rubber from the trees. Why? What were new inventions that would make the value of rubber rise so much?

Step 6 – How did these “examples” lead to European domination of the Congo?

- As reported by George Washington Williams – an African-American journalist who wrote a letter to King Leopold. He was informing the King of what his representatives were doing in order to gain territories from the Africans – he gave several specific examples:

- “A number of electric batteries had been purchased in London, and when attached to the arm under the coat, communicated with a band of ribbon which passed over the palm of the white brother’s hand, and when he gave the black brother a cordial grasp of the hand, the black brother was greatly surprised to find his white brother so strong, that he nearly knocked him off his feet.… When the native inquired about the disparity of strength between himself and his white brother, he was told that the white man could pull trees and perform the most prodigious feats of strength.”

- “The white man took a percussion cap gun, tore the end of the paper, which held the powder to the bullet, and poured the powder and paper into the gun, at the same time slipping the bullet into the sleeve of the left arm. A cap was placed upon the nipple of the gun, and the black brother was implored to step off ten yards and shoot at his white brother to demonstrate his statement that he was a spirit, and, therefore, could not be killed. After much begging the black brother aims the gun at his white brother, pulls the trigger, the gun is discharged, the white man stoops . . . and takes the bullet from his shoe!”

- The Europeans also often gave bottles of gin to the leaders

Step 7

- King Leopold never saw a drop of blood and never stepped foot in the Congo.

An account in 1884 describes the actions of an officer against those who refused to collect rubber or failed to meet their quotas – “I made war against them. Once example was enough: a hundred heads cut off, and there have been plenty of supplies ever since. My goal is ultimately humanitarian. I killed a hundred people… but that allowed five hundred others to live”

There was no written language in the Congo when the Europeans arrived – therefore, history is skewed, as, instead of African voices, there is largely silence.

8 million dead (most likely much more) in this one nation – comparison to Jewish Holocaust. Why is this not in the textbook?

Step 8 – role of propaganda and the importance of media literacy

- Henry Stanley – “American” journalist – was actually from Wales and was a bastard – he even changed his name.

- He fought on the side of the Confederacy during the Civil War and was captured at the Battle of Shiloh. He was sent to a prison camp in Chicago where he was promised freedom if he fought for the Union – which he did. He was assigned to the USS Minnesota that wound up shelling a Confederate fort – so he fought on both sides.

- Livingstone was a celebrity – he had “explored” throughout Africa and was the first all-white to cross Africa from coast to coast. He disappeared for five years on another journey – Stanley set out to find him.

- Leopold II – was largely ignored by his father growing up and was left to his own devices. He was only the second ruler of Belgium – a newly independent country. He thought the country to be too small (half the size of West Virginia) and wanted to expand his kingdom through imperialism. He was also upset that kings were losing power to constitutionalism and wanted more power – his own colony would allow him full autonomy.

- Eventually, Leopold used Stanley to do his bidding and set up a one-man colony under the guise of philanthropy.

Step 9 – Video – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o5z4M1dPYZ4 . I ask the students to pay particular attention to the museum curator towards the end and why he thinks that having a museum paid for and dedicated to Leopold is acceptable.

________________________________________________

In AP Euro, I took this lesson a bit further and had the students read and annotate Mark Twain’s King Leopold’s Soliloquy – the entire text can be found online http://diglib1.amnh.org/articles/kls/twain.pdf – I print it and have the students mark up the text and answer the following questions when they complete the reading:

King Leopold’s Soliloquy – Mark Twain

Answer these questions on lined paper – you do not have to rewrite the question, just write your answers after the number. Be sure to give specific textual evidence to back up your answers.

- What questions do you have?

- What sources were made to make the argument against Leopold by Mark Twain?

- Bullet some of the evidence amassed of the atrocities – include the page number from the writing

- List Leopold’s defensive arguments

- How did Leopold stop information of the atrocities from becoming widespread?

- What was the one form of media Leopold could not stop? Why?

- What makes Leopold II’s actions different from other rulers?

- Why was Leopold not tried for his crimes?

- What one item stuck out to you the most, why?

- How many died?

- How does this compare to the Jewish Holocaust?

– it is important to allow students to discuss in small groups after they have had a chance to write down some ideas. Ask for textual evidence when students volunteer to the large group discussion.

– it is important to allow students to discuss in small groups after they have had a chance to write down some ideas. Ask for textual evidence when students volunteer to the large group discussion.